|

As a preface to this blog post, kindly reference my posts from October 14, 2018 and August 12, 2023 regarding the late jazz vocalist Helen Carr for additional background and contextual information regarding the event described here.

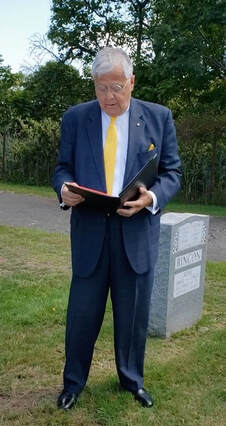

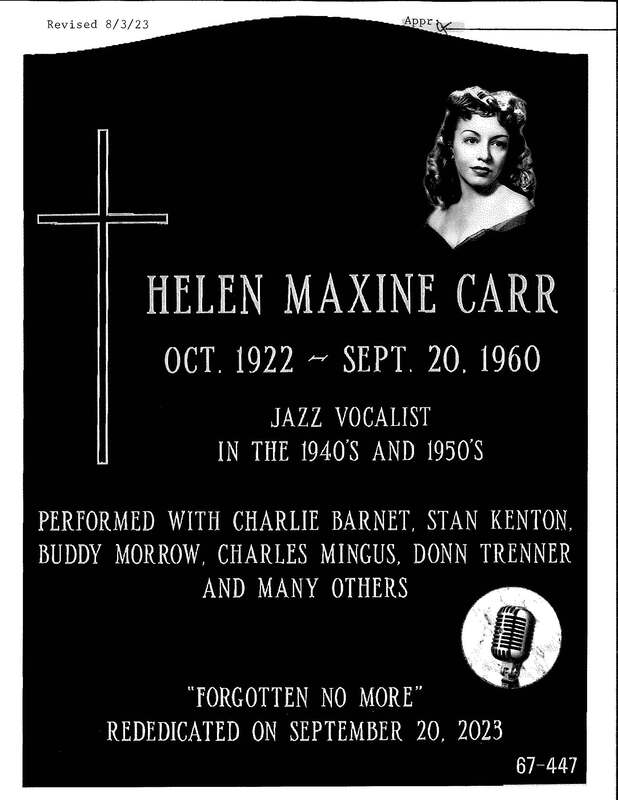

When she died, it appears it was left to her son Gordon to handle her funeral arrangements, and she ended up here. Her son Gordon was just 18 years old when she died, stationed at Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn with the U.S. Army. Gordon died in 1988, and we have very little information about him. I came out to this site a few years ago in an effort to see if Helen Carr’s date of birth was inscribed on her gravestone, as I could not find any record of her birth date - and it was at that time that we discovered that her grave was not marked. So Ms. Carr’s niece Jean, and I, both knew we needed to mark this grave - and that’s what brings us here today, We don’t know what kind of funeral service Helen Carr was given here 63 years ago. We do know that she was raised as a Christian as a youngster, and we are here to provide her with a Christian service today as we dedicate her grave marker. St. Luke’s Lutheran Church is a Church of which I was once a member back in the 1980s, and it’s located only three blocks from Helen Carr’s last Manhattan residence. It’s a wonderful place of worship that just celebrated its 100th anniversary, and we’re very honored and privileged to have Dr. Arden Strasser join us for today’s service."

© 2024 David Nogar All Rights Reserved

2 Comments

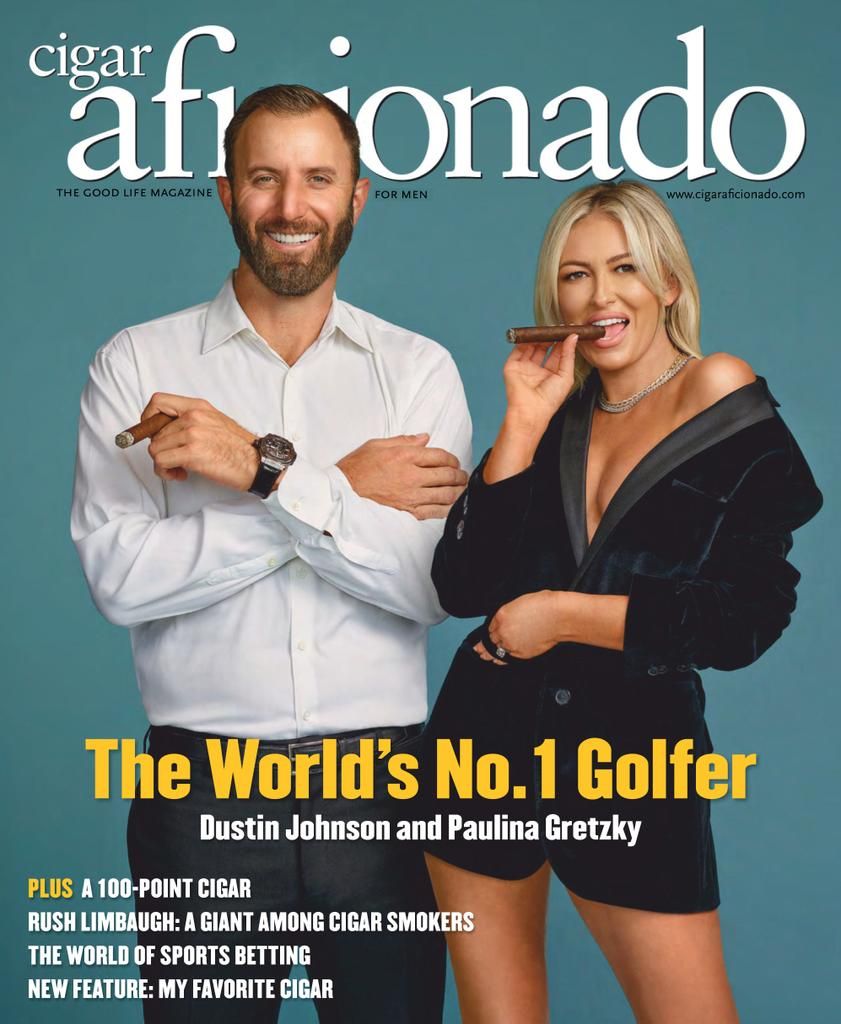

Mention the enjoyment of a fine hand-rolled cigar these days, and many if not most, will take a disdainful look at the person suggesting the enjoyment of something so unhealthy, smelly and unsightly. After all, the stereotype of the middle-aged, overweight, sweaty male, chomping on a stogie, will no doubt fulfill the image most non-smokers may have of your basic cigar smoker. About 5% of American adults currently smoke cigars. 8% of those cigar smokers are male; about 2% are female – and that number is growing annually. For example, about 7.6% of all U.S. high school students smoke cigars; but 6.2% of all female high school students smoke cigars on a regular basis – more than three times as many adult females. These figures come directly from the CDC.

Take it for what it’s worth. From this point onward, this article is for those who remain open to new sensory, life experiences that have proven themselves for hundreds of years – and how to make the most of them. What to Smoke The selection today of quality, hand-rolled cigars is enormous. If you’re new to cigar smoking, my advice would be to try as many as you can so that you can ultimately settle down on what you truly like. And you won’t know until you come across it. Cigars come in all shapes, sizes, strengths, characteristics and flavors. Everyone’s tastes are unique – and cigars will be no exception. My own personal favorites include:

In my opinion, you can’t go wrong with any of these. Each one has its own unique characteristics, aroma and flavors. Any Padron, and to a somewhat lesser extent, Davidoff's The Late Hour for example, always have an easy draw, good even burn, and they put out plenty of smoke. The Partagas D5 is currently my favorite Cuban cigar. The Macanudo Gold Label is an exceptionally mild smoke with a velvety texture on the tongue and in the mouth. The Cohiba Siglo VI isn't a bad smoke, but thanks to the recent extortionist pricing policy of Habanos S.A., the state-run tobacco company in Cuba, the Siglo VI is now going for about $130 a stick - and it is positively not worth the money. You're better off going with any of the other favorites I identified above. If you must smoke a Cuban, I would definitely recommend any Partagas Serie D. If there is a particular cigar you think you’d like to try, but are unsure if you will like it – look-up the cigar online and read some reviews to get an idea of the flavor and aroma notes of it. But also don’t be afraid to try something completely unknown. Pairing With Spirits and Other Beverages

For a straight spirits accompaniment, try a McCallum 12 or 18, Dalmore Cigar Malt, Knob Creek bourbon, Weller's 12-Year bourbon, Martel Blue Swift or cognac, or maybe even some 15 or 21-year Appleton Estate Jamaican rum (if you can find it), all on the rocks. Every different combination will be a rewarding experience. Interestingly, one beverage that gets mentioned consistently as being excellent to pair with cigars is coffee - especially expresso. I have also often paired with craft soft drinks such as artisanal root beer, vanilla cream or black cherry soda, or cola – all with excellent results on a hot day. And yes, Coke works just fine - at least for me. Pairing with Food

No Hard and Fast Rules The main thing to keep in mind however is not to be reluctant to try as many different cigar-drink-food pairings as you can. They are as infinite and complex as wine and food pairing – and arguably more versatile. Don't forget, cigar tobacco - like wine - varies by climate, soil conditions, the aging and seasoning processes used, and the techniques used by the torcedors in a given location or country. So give this a try. Sitting outside on a cool summer evening with a fine cigar, quality whiskey, and some cool jazz playing in the background..... it's quite hard to beat. I've had some of my most profound thoughts about life during these sessions. Cheers! © 2024 David Nogar All Rights Reserved

This blog post is about three years late. Almost five years ago, I did a blog post regarding jazz vocalist, Helen Carr, which can be found here. It was really only intended as a one-time post to provide some information about a little-remembered vocalist of whom very little information was known - despite the fact that she recorded with many significant jazz artists of the day, and still has two albums in print. That post prompted contact from Helen Carr’s niece, who lives in Washington state. I won’t mention her name here out of respect for her privacy. During the course of our communications, she very graciously provided me with additional information and assistance regarding her aunt, which prompted me to do further research. Despite some conflicting information on the Internet, Helen Carr died from complications resulting from cancer at 4:20am on Tuesday, September 20, 1960 at Roosevelt Hospital in Manhattan, which is now part of Mount Sinai West, located two blocks west from Columbus Circle and Central Park South. She did not die in an automobile accident as has sometimes been reported. The mortuary handling her burial was the Joseph T. Kennedy Funeral Chapel at 941 Amsterdam Avenue, about seven blocks north of the hospital. For some reason however, arrangements were made to bury Helen Carr at Rose Hill Cemetery in Linden, New Jersey on September 24th. And that is where she is today. It appears it was left to Helen’s son Gordon to handle all of the funeral arrangements. At the time, Gordon Carr was serving in the U.S. Army at Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn. He himself passed away in New York City in 1988 at the age of 42. I made a trip out to Rose Hill Cemetery several years ago to see what additional information might be gleaned from the inscription on her gravestone. To this day for example, no record of Helen Carr’s birth can be found, and no one in her family today knows the actual date of her birth. I thought this information might be found on her gravestone. However, when I got to her plot, I found that there is no gravestone. Helen Carr is buried in an unmarked grave. So at this point in her life, it appeared that Helen and her son had each other - but it seems that was pretty much it. Consequently, lack of funds for a more elaborate burial may very well have been an issue. Nonetheless in surveying the situation out at the cemetery, I just knew we couldn’t let it stay this way. I can imagine few things sadder than struggling and scraping to achieve the dreams and ambitions of your youth, only to die at the very young age of 37 - probably alone - and to be buried in a place where there’s nothing to mark your resting place. Surely Helen Carr deserved better than that. So, I informed Helen’s niece of what I found, and we worked together to do the right thing. Without her support and approval as Helen’s closest living relative, we would never be where we are today.

© 2024 David Nogar All Rights Reserved

The past six months have certainly been interesting ones, to say the least. At no time in human history has a respiratory disease been used as a pretext - on a global scale - for curtailing civil liberties, driving millions into unemployment - not to mention the permanent closure of hundreds of thousands of small businesses. And of course, let's not forget the 'mandatory' mask mandates by government fiat. We are told to avoid handling cash. Too easy to spread the virus that way, they say. Instead, use only credit or debit cards, so that there is an electronic record of every one of your purchases. Is it a coincidence that promoted or mandated exclusive use of these cards can also provide for direct, 3rd party control over your money, when the appropriate time comes? We're being told to acclimate to a 'new normal.' But what will such a 'new normal' look like? Permanent masks while in public? Will bars and restaurants, as we know them, ever be allowed to open again? Will we ever be able to go to the theater or to a jazz club again? Perhaps not until we're all forced to take a mandatory vaccine? For a flâneur who wants to savor life, as well as enjoy and appreciate those with whom he/she shares humanity - these are ominous, if not sinister times, indeed. But these are all rhetorical questions, which may or may not be answered as events continue to unfold, and are not within the scope to address here. Those questions will be discussed at length in subsequent posts as we explore the real reasons we find ourselves trapped in this new reality of the year 2020. And trust me, it's a rabbit hole as deep and as sinister as it gets. For now, the question at hand for this post then is, given the circumstances of our new reality - what is a flâneur to do? The first and most basic element in flânerie is Social Interaction. Social Interaction has been significantly curtailed over the past six months due to: our virtual house arrests since mid-March; the mask mandates; and the apparent mass neuroses of getting too close to other human beings for fear of contracting the COVID-19 contagion. It's hard to imagine a more effective combination of factors that could be as damaging to our common humanity and bonds to one another, than by establishing these artificial, and mostly unwarranted barriers. #socialengineeringatitsworst We're not going to get into the reasons for this here, as I previously mentioned, but rather we'll talk about how to still get the most out of life as a flâneur under these most trying of circumstances. 1. Social Interaction (with Those Closest to You) If you lost your job or other income as a result of government actions in response to the virus, hopefully you have been able to obtain unemployment or small business assistance and other special considerations for paying your monthly expenses until you can return to generating other income or wages and catch-up - or otherwise resolve your outstanding financial obligations. Particularly if you have a family, this will be an overriding consideration until these life circumstances change. Sometimes life throws overwhelming challenges at us, and certain things must be set aside until we can stabilize or situation - but that doesn't mean we have to stop living. In the meantime however, most of us will be spending more time than ever at home, and this provides us with a unique opportunity in which to spend much more quality time with our families, as well as for our own introspection and intellectual pursuits. My wife an I spend an evening cocktail hour out on our front terrace every day, weather permitting. It provides us with an opportunity to spend time together that we would ordinarily never have time to do - giver our pre-lockdown work schedules. Therefore, try to turn this situation into a positive experience if you can, by rediscovering your own spouse or family.

© 2020 David Nogar All Rights Reserved

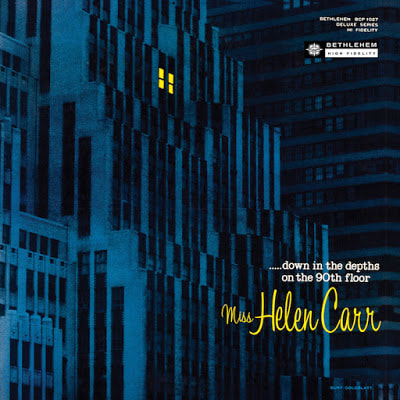

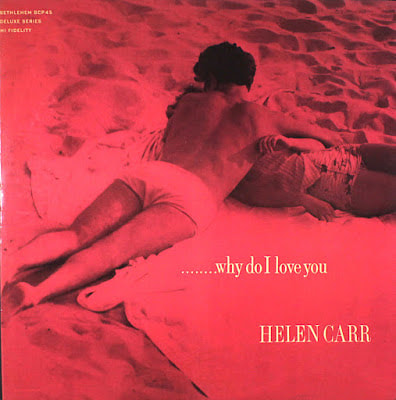

“With a million neon rainbows burning below me And a million blazing taxis raising a roar Here I sit, above the town In my pet pailletted gown Down in the depths on the ninetieth floor…" - An excerpt from a composition by Cole Porter, written for the 1936 Broadway musical, Red, Hot, and Blue When one comes across the name Helen Carr, to many people it often has a very vague ring of familiarity to it. Who was that? Was she in films? In music? But in reality, most people don’t know Helen Carr. Nor have they probably seen or heard any of her work. To those who know of her, she has an aura of legend and mystery – principally because there is so little known about her, and because of her premature death – the cause of which very little is also publicly known. Helen Carr was a jazz singer. The actual location of her birth presently remains undefinitive, although both the 1930 and 1940 U.S. Census records record her birthplace as Utah, and the liner notes of her Bethlehem album, Down in the Depths of the 90th Floor further confirm that she, "hails from Salt Lake City." However, no corroborating documentation has yet been found. Various sources report multiple dates for the year of her birth, ranging from 1922 to 1928. Her second husband, pianist Donn Trenner indicated that she had, “…never been honest about her age.”[1] My guess is that October, 1922 is probably the most accurate date based on U.S. Census records and private family correspondence, making her five years older than Trenner. Helen Carr, Sammy Herman, Joe Bianco and Donn Trenner in New York City, February 1947 Photograph by William F. Gottlieb She was attractive and had a pleasing voice, but she would not be my favorite type of jazz singer. Her voice was soft and breathy – almost sounding like a bluesy Marilyn Monroe. She was clearly a mature singer who was in command of her material and was quite poised on the bandstand. Donn Trenner opined that he could hear the influence of Billie Holiday in her voice. I think that’s a bit of a stretch, but she did have a sultry quality, and she could interpret music with great feeling.[2] The jazz vocalists I truly prefer are always women, but are also those who can project with great clarity – and who can swing – even on ballads. That is why my favorite will probably always be Ella Fitzgerald, followed very closely by the best jazz vocalist working today, Vanessa Rubin. When Donn Trenner first met Helen Carr, it was on a double-date with Jimmy Hanson, a tenor saxophone player with the Ted Fio Rito band in 1945. They had just finished their gig at the Golden Gate Theater in San Francisco, and drove to the Mondre Café in Oakland with two women they had met earlier. Trenner was driving the car, and when he looked at Helen Carr in the rear view mirror seated on the back seat with Hanson, he knew that she was the woman he really wanted.[3] At the time, she was an operator for, “… a telephone service in bars and late-night clubs where one could dial-up a song. You told the operator what song you wanted to hear and they would play it from their central station.”[4] Shortly thereafter, Donn Trenner was drafted into the military, but he continued to date and remain in touch with Helen Carr. At one point he was transferred to Scott Air Force Base near Belleville, Illinois about 25 miles east of downtown St. Louis, and Helen moved to the Midwest to be near him. The Chase Park Plaza Hotel in St. Louis, Missouri and accompanying Steeplechase Room - just one of a number of entertainment venues that have been part of this iconic hotel for decades. She moved into a place next to the Chase Park Plaza Hotel in St. Louis. According to Donn Trenner’s autobiography, “They had a venue called the Steeplechase Room with a trio lead by a great guitarist, Joe Schirmer. That’s where Helen learned one of Cole Porter’s lesser-known songs, “Down in the Depths of the 90th Floor." The song has three different segments; it’s not written as a standard thirty-two bar song form. It tells a story, which requires a distribution of different emotions within the lyric content.”[5] That song became one that is most associated with Helen Carr, as hers is arguably the definitive version – in much the same manner as Artie Shaw’s version of Cole Porter’s “Begin the Beguine” is certainly the most definitive version of that. Interesting to note, by-the-way, that neither song follows the standard 32-bar format. When Donn Trenner was discharged from the military in the autumn of 1946, he and Helen Carr moved to New York City to a small flat on West 86th Street and began looking for work. Several months later they eloped, getting married in Elkton, Maryland.[6] But unfortunately from the outset, even before they got married, there were behaviors exhibited by Helen that ultimately doomed the marriage. According to Trenner, she, “… reacted in negative ways whenever she was in the presence of other women.” He at first attributed it to insecurity, but he soon realized that it was more than jealousy, and characterized it as a neurosis.”[7] Remember too as noted earlier, the wide variation in her reported dates of birth, as she frequently, apparently misled about her age. I won’t elaborate on this behavior in terms of her jealousy and mistrust any further here, but for those who wish to research this aspect of Helen Carr’s life further, I would refer you to Donn Trenner’s autobiography. During this period, Donn Trenner claimed he could only play with bands where a spot could also be guaranteed for Helen Carr, or things just wouldn’t work out given her behavioral issues. They played with Blue Barron and Chuck Foster, and ultimately got a call to join Buddy Morrow in 1947. After the work with Buddy Morrow ended in 1948, the couple moved back to San Francisco where they had first met, and where Helen had a child named Gordon from her first marriage still residing. Even at this point, Trenner claims that he did not know much about Helen Carr’s past.[8] An East Coast edition of The Donn Trio and Helen, featuring Sammy Herman and Joe Bianco, in New York City. The West Coast, and presumably original edition of The Donn Trio and Helen, with John Setar on reeds and Tony DeNicola on drums, late 1947 or 1948. Once back in San Francisco, they put together their own group, known as The Donn Trio and Helen, which was together for about a year when Charlie Barnet made the couple an offer to tour with his big band, which they did during 1950-51. This resulted in Helen Carr’s only known filmed performance, a Snader Telescription, which also included Donn Trenner playing piano. The only known filmed performance of Helen Carr, here with Charlie Barnet & His Orchestra, and with Donn Trenner on piano. There was some excellent research done on the Obscure & Neglected Female Singers of Jazz & Standards forum that indicated while in San Francisco, an article in the Oakland Tribune on Friday, July 22, 1949 reported that Helen Carr was awarded five weeks’ custody of her son who was living in a foster home after her divorce from her first husband, Walter A. Carr, a chef in Orinda, CA on November 24, 1947. (Note that according to Donn Trenner’s autobiography, they were married in Elkton, Maryand in late 1946 or very early 1947.)[9] The California Birth Index indicates that Helen’s son, Gordon William Carr, was born on August 2, 1942, and that Helen Carr’s maiden name was Huber.[10] The Oakland Tribune on Friday, June 13, 1941 recorded a marriage license issued in Reno, Nevada to Helen M. Huber (age 19) and Walter A. Carr, both of Oakland. So that, along with the 1930 and 1940 U.S. Census records, would seem to solve the mystery of her birth year (e.g., 1922).[11] Researching her name in the 1930 and 1940 Census and other newspaper records indicate that she was living with her parents in Danville, Illinois in 1930; in Kansas City, Missouri when her father died in 1936; in Seattle, Washington with her widowed mother in 1940, working as an usherette in a theater; and finally shown as being registered to vote in Alameda County, California with her mother by 1944 (though married in 1941).[12] After leaving Charlie Barnet, Donn Trenner worked with Les Brown from 1954 to 1961. Helen was not part of the band, but she did travel frequently with her husband. During this period however, she picked up recording gigs and club dates when she was able, including two record albums for the Bethlehem label in 1955. The first being, Down in the Depths of the 90th Floor, followed by, Why Do I Love You. Interestingly, her picture never appeared on either album cover.

While in Philadelphia finishing an engagement with Oscar Pettiford and Anita O'Day, three days before Mothers’ Day, Trenner was in a greeting card store looking for a card for Helen when he was approached by a woman who asked him if he was ‘all right’ because he looked rather sad. They spoke for a few minutes, and while he claims she wasn’t soliciting for a date, she left him with a card that had her name and telephone number written on it in case he needed someone to talk with. While back in his hotel room, he was writing a thank you note to the woman when Helen, who had been in New York, unexpectedly arrived at his room to drive him back to Manhattan. So he shoved the half-written note under a pillow, and of course his wife found it.[13] A very bad move indeed. All of this only reinforced Helen Carr’s mistrust in him. Nonetheless, they headed off back to New York from Philadelphia in their blue Buick, and an argument ensued in the car, to the point where she was apparently beating Trenner over the head with her shoe while he was driving. As he approached the toll plaza to the Pennsylvania Turnpike, he pulled off to the side of the road, dove out of the car and ran for cover in some bushes, all of this occurring at about 2 o’clock in the morning.[14] According to Trenner, she drove back and forth several times looking for him while he was hiding in the bushes, until finally getting on the Turnpike and returning to New York alone. Trenner returned to Philadelphia for the night. The woman with whom Donn Trenner spoke in the greeting card store was named Joan Martin, who also happened to be a close friend of Chan Parker, Charlie Parker’s wife. Chan lived in New Hope, Pennsylvania and owned an ice cream parlor called the Bird’s Nest. That was where he ultimately found Joan Martin who came back to Philadelphia and took Trenner to her apartment until he returned to New York. While back in New York, Trenner claims he found papers proving that Helen Carr had never gotten divorced from her first husband (although this would appear to be contrary to the Oakland Tribune article from 1949), so he was able to get his marriage to Helen annulled. All of this would have been around 1958. Chan Parker married Phil Woods shortly thereafter (Charlie Parker died in 1955) and left New Hope, PA for France in 1959.

This young girl, who lost her father at about age 14, and who traveled around the country with her mother until ultimately settling in northern California, became a big band and a club jazz singer who recorded two albums that were reissued on CD, and that are still in print – almost 60 years after her death. And there still remains a cadre of jazz researchers and aficionados who want to ensure that this lady – this sensitive and talented human being, is not forgotten. And a worthy aspiration that is, indeed. Rest in true peace, Helen Carr. Manhattan, I'm up a tree The one that I've adored Is bored With me Manhattan, I'm awfully nice Nice people dine with me And even twice Yet the only one in the world I'm mad about Talks of somebody else And walks out With a million neon rainbows burning below me And a million blazing taxis raising a roar Here I sit, above the town In my pet pailletted gown Down in the depths on the ninetieth floor While the crowds at El Morocco punish the parquet And at 21 the couples clamor for more I'm deserted and depressed In my regal eagle nest Down in the depths on the ninetieth floor When the only one you wanted wants another What's the use of swank and cash in the bank galore? Why, even the janitor's wife Has a perfectly good love life And here am I Facing tomorrow Alone with my sorrow Down in the depths on the ninetieth floor. Down in the Depths of the Ninetieth Floor Composed by Cole Porter in 1936 NOTES [1] Donn Trenner and Tim Atherton, Leave It To Me… My Life In Music (Albany, GA: BearManorMedia, 2014), 54. [2] Ibid., 29. [3] Ibid., 23. [4] Ibid., 23. [5] Ibid., 29. [6] Ibid., 31. [7] Ibid., 31. [8] Ibid., 34. [9] http://forums.stevehoffman.tv/threads/obscure-neglected-female-singers-of-jazz-standards-1930s-to-1960s.588217/page-38 [10] Ibid., 38, post by Eric Carlson. [11] Ibid., 38, post by Eric Carlson. [12] Ibid., 38, post by Eric Carlson. [13] Trenner and Atherton op. cit., 53 [14] Trenner and Atherton op. cit., 53 [15] Trenner and Atherton op. cit., 55 © 2018 David Nogar All Rights Reserved

“Now is the winter of [my] discontent, made glorious summer by this sun [that is New] York.” - with deepest apologies to William Shakespeare, for bastardizing his opening line from, Richard III; (not to mention John Steinbeck), however, the relevance of the re-wording should become apparent below. It has been over eight months since my last blog post. There is a reason for this. I have spent the time adjusting to a very difficult new phase of my life – reconciling the realizations, failures and disappointments of the past two years into a positive path forward that will allow me to rebuild momentum in a clear direction and, perhaps above all else, continue to lead the life of a self-professed flâneur who does his best to bless others through his interactions with them. Being a sexagenarian has been a most interesting experience. In working my way up to it, I often heard the term, “golden years,” applied to this period of life, and wondered how that “gold” would manifest itself in my own. I’m a little less than halfway through this ‘golden’ decade now, and to be brutally honest – I expected something much better. It fact, it’s probably been the most unhappy, unsatisfying period of my entire life. At least so far.

As a consultant, I work for a large worldwide firm, and I’m making more money now than at any other time in my career. And I hate every single minute of it. I feel like a whore who pimps himself out for an hourly billable rate, and I see nothing substantive, constructive, or certainly fulfilling, coming out of my billable activity and, more importantly, my remaining time in this life. But yet I continue to do it. Why? Two reasons primarily: 1) the money – and the unwillingness (at least until now) to live on less; and 2) the knowledge that my professional working career for all intents will be over forever once I quit because of my age. I think that pride has a lot to do with it too. I've had the privilege of being able to hold so many responsible positions during the course of my career, that I guess I'm having a hard time reconciling myself to the fact that this is not the way I thought it was all going to end. But we also have no business defining our value as humans through something as superficial (especially in today's crass and narcissistic work environment and culture) as job stature - do we? It's important not to fall into the same trap as perhaps Ethan Allen Hawley from the Steinbeck novel, isn't it?  I also lost a very cherished friend through circumstance, who had provided me with critical emotional support and camaraderie through this period. That loss created a profound emptiness and sadness for me, and I think that’s the point at more than any other time where I really lost my sense of direction, and truly settled into a mindless, depressive routine that’s quite similar to that of a prison work release program: get up; go to work; return home; grab something light to eat; go to bed; get up…. Don’t think about anything else. Just do what you have to do, and get it over with – until the next day. Until you die. Or quit. Such a routine transforms one’s life from truly living in every moment – to just putting in time. And I’ve been horrified to learn that time fast forwards exponentially when you do that. It is precious time wasted, that can never be regained. I cannot believe it’s been over 8 months since my last blog post here. That, shall never happen again. And the power to ensure that rests solely with me. It’s just a matter of making the necessary adjustments to one’s life expectations in order to pursue the true calling. Most of us get wrapped up in this 'game of life’ - that ubiquitous treadmill that ensnares us, fills us with unnecessary desires that make others wealthy, siphons off our time, and sucks us dry through virtually our entire lives. It takes courage to flip the table over, get up, and walk away. That’s what I’ve decided I have to do.

However, such an offline sojourn as this recent one was useful at least in this instance, to help me understand the consequences and imprudence of veering away from the very premise of my blog and website in the first place. That confirmation was definitely needed by me in 2018. And my absence also reaffirmed the pitfalls of social media that I spoke about in laying out the foundations for this blog and website. Don’t live in your smartphone. Live in reality. Go to a bar. Order a drink. Start talking to the person next to you. Turn the phone off. Do something - or at the very least enrich someone's life, even just a little bit, through your interaction with them. You know, I read so many platitudes that people post on their social media pages. So much of it is all the same basic 'let-me-convince-myself-I'm-really-happy-because-I-say-or-think-this' kind of stuff. Everybody seems to be searching for an answer. It’s as though we’re all unhappy. We’re all depressed. We’re all looking for things to get better. Well, what if things aren’t going to get any better? What if, as Jack Nicholson posed the question in the 1997 film, this is truly “as good as it gets?” Trust me. You won't find happiness or fulfillment in your smartphone. All you will do is waste precious time. Follow the desires of your heart instead. Anyway, I did make some good friends over the past 18 months. Ironically, they’re virtually all bartenders. I guess that’s all you need to know about the current state of my mind. So the summer in New York was not without its rewards – including the discovery of some outstanding venues for food, libations, entertainment, and most importantly, social interaction, which will all be reviewed on these pages in upcoming months. If I’m lucky to live as long as my father, I have about 10 years in this life left. That time will fly by in a blink of an eye. How do I really want to spend it? Certainly, not like the last two years, especially. I think I now know. The American Flâneur has, in a manner of speaking, returned. So with the end of summer, comes the autumn and then the winter. And with it, hopefully the ultimate end of the discontent, depression, and what the French call ennui, so that by next spring, the disappointments and sadness will be far behind me, as I move forward down that final stretch, with a renewed sense of purpose and energy. © 2018 David Nogar All Rights Reserved Well, another New Year's Eve is now behind us, and the famous ball high above New York's Time Square has dropped the 141 feet in 60 seconds yet again, heralding the beginning of another year. While most of the world is no doubt quite aware of this annual event in the heart of midtown Manhattan, one is sometimes prompted to ponder to how many people have actually experienced the dropping of the ball in-person.

The tradition of the ball drop at New Year's Eve in Times Square actually began 110 years ago, with the 1907-08 holiday season, which was instituted by Adolph Ochs, who at that time was the publisher of the New York Times. Prior to that, he had used fireworks to herald the beginning of each new year at the newspaper's headquarters at 1 Times Square. To date, there have been a total of six balls used over the past 110 years, with the original one being five feet in diameter, constructed of wood and iron, and illuminated with 100 incandescent light bulbs. The original ball was manually hoisted up the pole by a team of six workmen, and weighed 700 pounds.

The line for the Waterford Crystal cocktail reception queued along 42nd Street to the private elevator lobby. The photo at the right would be the author polishing the Waterford Crystal panels with a flourish using his pocket square. No Windex, however. All of this is to say, that the Times Square Ball has a rather interesting history, and is frankly worth checking out if you get the opportunity - but not on New Year's Eve.

For me, I prefer a quiet New Year's Eve, normally in the solitude and comfort of my own home. I like to reflect on my blessings of the closing year, and to plan for the new year in a way that will allow me to improve as a human, and to make the most beneficial, productive use of my time - as our tomorrows are never guaranteed. Parties with good friends are always great. But for me at least, not on Amateur Night - which occurs regularly on December 31st. And so, to all of my family, friends and readers, I wish you all a healthy, happy, safe and prosperous New Year, filled with all of the blessings life can bring. © 2018 David Nogar All Rights Reserved Rod Serling is one of my favorite writers. While he is still no doubt best known as the creator and host of the CBS television series, The Twilight Zone (1959-1964), he has produced a body of work that goes far beyond the scope of that series, with much greater depth, than most people are aware today – that is, for those who even remember him. Born in Syracuse, New York on Christmas Day in 1924 to a Jewish family (but later converting to Unitarianism), he spent most of his youth 70 miles to the south in Binghamton, when his parents moved there in 1926. This apparently was a most idyllic time of his life, as he reminisces upon this period as a golden, innocent age in America, time and time again in his writings. After graduating high school in 1943, he enlisted in the Army Air Force, in the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 11th Airborne Division. After undergoing basic training in Camp Toccoa in Georgia, his division shipped out to New Guinea, ultimately seeing action in the Philippines and was part of the occupation force in Japan. He saw death around virtually every single day during his tour-of-duty in the Pacific. He was wounded twice in the Philippines, and was awarded the Purple Heart, Bronze Star and the Philippine Liberation Medal. But despite his distinguished service, the war in the Pacific left an indelible mark on him – shaping his political views and writing (as well as leaving him with flashbacks and nightmares) for the rest of his life. Once discharged from the Army in 1946, and after a period of recuperation, he enrolled in Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio where he ultimately studied theater, broadcasting and majored in Literature, graduating in 1950 – pretty much at the dawn of the Television Age. Rod Serling’s true skill as a writer, in my opinion, was as a dramatist. As actor Jack Klugman once opined – he had a marvelous way of using words in terms of phrasing dialogue. The dialogue he wrote was always natural, poignant and virtually rolled off the actor’s tongue. He had a tremendous empathy in his writing for the downtrodden, oppressed, and poor in spirit. In that regard, his writing reminds me very much of John Steinbeck.

In the 1950s, many television dramas were actually broadcast live. This is the first television drama where the critical and popular acclaim was so great, that the performance was repeated – but it actually had to be performed and broadcast again as a separate performance, because it was live! Ironically, the theme here was not too dissimilar from Rod Serling’s last great teleplay of his career, “They’re Tearing Down Tim Riley’s Bar.” Here, he has come full-circle – from the ‘newcomer’ in, “Patterns,” to the tired, lonely businessman getting pushed out, only 16 years later in, “They’re Tearing Down Tim Riley’s Bar.” [2] Subsequent to his success with, “Patterns,” in 1955, he wrote a number of award-winning, outstanding teleplays and screenplays, including: “Requiem for a Heavyweight” Playhouse 90 (1956); “The Comedian” Playhouse 90 (1957); “A Town Has Turned to Dust” Playhouse 90 (1958); “Seven Days in May” (1964); “Planet of the Apes” (co-written with Michael Wilson) (1968); and of course, many of The Twilight Zone and Night Gallery episodes. And this brings us to, “They’re Tearing Down Tim Riley’s Bar.” [3] Night Gallery Season 1, Episode 6 - "They're Tearing Down Time Riley's Bar" Teleplay by Rod Serling © 1971 MCA-Universal. All Rights Reserved Reproduced here for editorial and review purposes only. Given the importance of the cocktail bar as an institution of Social Interaction and as a principal venue for facilitating the pursuit of flanerie - a tenet established by this website - it is perhaps not too surprising that this story would revolve around the demolition of a bar that, in reality is the only physical remnant remaining of the precious memories of those long departed and cherished by the protagonist.

Not too unlike the madeleine that Marcel Proust dipped into his tea, which brought back the flood of memories resulting in Remembrances of Things Past, I think. I saw this episode when it was originally telecast on a Wednesday night, January 20, 1971. I was just 17 years old. And I was struck, and somewhat puzzled, by the pathos that it evoked in me, even as an adolescent. How could such a story have so profound an impact on a young man who would have never yet experienced any of these things? Perhaps some of the reason was simply due to the quality of the writing in this episode, which was nominated for an Emmy Award in 1971, along with the brilliant performance of actor William Windom as Randy Lane. But I also believe that I somehow innately knew (or perhaps feared) that much of the emotion and experience on display in this episode would be mine to experience in real life as an old man. And to a degree, it has. I now know why old men drink! It's quite fascinating to see as well how much of the modern human experience remains consistent from one generation to the next. And so now, 46 years later, I too, like Rod Serling, find myself also coming full-circle, with even more empathy for the protagonist – because I now understand completely much of his experience – particularly in the workplace. And while I’m blessed with a beautiful wife for which I cannot express enough thanks and gratitude, so many in my life who have meant so much to me, are now just simply gone. But their spirits touch me, everyday. And I think about them and I miss them, everyday. The ending for me however, will not be the same as the ending for Randolph Lane in the episode above. At age 62, I have truly come to the end of the road – at least in a corporate environment. For me, there will be no, “…next 25 years.” And that's quite okay. The real question to be asked is, "What's next?" For me, as I have consistently established in this website and blog, the only credible answer is to pursue the life of a flâneur – continually meeting new people through humble Social Interaction; enjoying and caring for the true friends I have; and savoring all of what life has to offer. And that is what we shall begin doing here. _____________________________________________ [1] Internet Movie Database (IMDB), “Patterns,” Kraft Television Theater [2] Gordon F. Sander, Serling: The Rise and Twilight of Television's Last Angry Man (New York: Penguin Books, 1994), 212. [3] © 1971 MCA-Universal. All Rights Reserved. Episode made available here for editorial and review purposes only. No copyright infringement is intended. © 2017 David Nogar All Rights Reserved This particular post isn’t for everyone. And that’s a good thing. Because the topic addressed here is something that I hope no one has to experience – though some of us, perhaps many of us, do – almost everyday. While this topic may seem rather morose to many – if it's actually helpful to even just one person, then the time put into it was well worth the effort, in my view. Despair is something that all of us experience at one time or another - often due to the loss of a loved one, or some other catastrophic life event. But with the passage of time, the intense pain of despair gradually fades, and life returns to some semblance of normalcy. Some despair however, never really fades away. It is chronic, and it can be completely debilitating, unless you find effective ways to deal with it. And so I will share a few rather personal experiences and perspectives, and how I have tried to effectively manage them in order to cope with the intense sadness that accompanies such despair, so that I might nonetheless proceed to live my aspirational life of a flâneur – a life of rich experiences, profound meaning, and one that is truly worth living. Depression vs. Despair It’s best to begin I think, by understanding exactly what despair is – and the difference between despair and depression. In depression, one feels sad or low for an extended period of time – and not necessarily for any discernible reason. In my case, I’ve personally experienced prolonged periods of great sadness, along with profound feelings of worthlessness; the inability to concentrate or focus intellectually; extreme fatigue or loss of energy; and recurring thoughts of my own impending death (though never suicide, thankfully). And there's never any real specific reason for such feelings, as those who suffer from such things know all too well. They just occur. While it may be hard to imagine – despair, specifically clinical despair – is actually worse than what's described in the previous paragraph. Because in addition to all of the above-referenced attributes symptomatic to depression, despair is also characterized as “…. a profound and existential hopelessness, helplessness, powerlessness and pessimism about life and the future…. [as well as] a deep discouragement and loss of faith about one's ability to find meaning, fulfillment and happiness, to create a satisfactory future for oneself.”[i] Most people who know me and work with me would probably be rather surprised to read the previous two paragraphs, and see me apply them to myself. That's because you learn to cope, and to manage, and to bury, so that you can move forward with your life. You must do this. There is no viable option. The only other alternative - which is not a viable one - is simply to allow yourself to become consumed and incapacitated by it. And for me, that just cannot be allowed to happen - although the battle becomes more difficult with each passing day. How I Developed Long-Term, Chronic Despair I believe my battle with depression had its origins with intense feelings of a lack of self-worth that actually began 50 years ago in adolescence. The oldest of two siblings, I was instilled with the notion that if I didn’t apply myself to my absolute fullest, there was a strong probability that I would simply grow up to be nothing short of a village idiot as an adult. Nothing I did at that early age seemed to be good enough. As a result, I lived a young life hearing mostly criticisms of myself, or how I failed to meet someone's expectations, with very little encouragement – or at least much that I can remember. But it's important to realize that such an upbringing, like so many other experiences in life, is never all bad - as it always ends up having both positive and negative influences. For one thing, it resulted in me setting very high standards for myself. I was always my own worst critic. But I also applied those same standards to others in those days, and frankly, even to this day sometimes, which unfortunately often makes me harshly judgemental of others, and occasionally even completely dismissive. On the plus side, that upbringing made me extremely self-reliant (e.g., Because why would anyone think enough of someone like me to want to do anything for me? Ergo, anything I got in life, I would have to obtain for myself. So that's just what I did.) It also made me a very independent thinker, because I 'knew' that I couldn’t rely on anybody else for positive reinforcement. As a result, I wasn't very much influenced by others. I always had to think things out for myself. Consequently, my mindset also essentially made me bit of an over-achiever.

Having said all of this, it’s also important to state here unequivocally that my family was a loving one, with parents who did their absolute best to raise two sons under challenging financial circumstances – which they did. I will always be grateful for the sacrifices my parents made for me, and I will always love them. All any of us can do in life, is the best we can, with the hand we're dealt.

But I nonetheless went through most of my life unable or unwilling to form strong bonds with any other human being. Yes, I dated of course, and I had acquaintances, but nobody was ever truly “let in.” And that frankly made for a very lonely and often sad personal existence. Even my beloved wife of over 20 years, who has truly become my best friend and my life, has often lamented in frustration that I continuously “live inside my head.” Daily Functionality Under Despair But as I mentioned earlier, we all have to make the best of our circumstances. We all have to find ways to cope and move on with life. And that's precisely what I did. It has always been remarkable to me just how successful – at least to a degree – one can actually become, even amidst much dysfunction. If you’re reasonably adept at discerning the expectations within your work environment, and you have even a modicum of competence, you can actually go quite far in business - to a point. Where you'll hit the ceiling, is the path from the senior management level to the executive level. Because the executive level is a club. And membership to the club is built upon the personal relationships and alliances you’ve built along the way. If you cannot, or you are unwilling to forge those relationships, membership in the club is probably not in your future. The club is also generally not for independent thinkers. So if you fancy yourself a maverick of sorts, that’s perfectly fine – just appropriately adjust your expectations as you attempt to career path. But I digress. Pursuing a successful career path is really not the primary reason for this blog post. I make the point only to illustrate that you can outwardly appear successful to others, but inside there can be a pain and emptiness that will ultimately destroy you if you allow it, and if you do not act to manage it. As I very clearly point out in the Social Interaction section on the Elements page of this website, “To go through life minimizing our interactions with others is to miss out on what most of life has to offer…” I, in fact, made that mistake for most of my life. I essentially admit it in that section. But my point here is that when you do what I did, for as long as I did it, there are long-term consequences to your mental well-being that can permanently impact your ability to find happiness and fulfillment in your life. As I also previously recounted in that same Social Interaction section, it was a full dozen years after the death of both of my parents, while in my late 50’s, that it finally dawned on me what I had been missing out on my entire life. And that reassessment of my life, along with how to more appropriately live it, ultimately manifested itself in the creation of this website and blog, in order to share the benefit of my experiences with other like-minded persons who know exactly what I’m talking about, or who are searching for the same things. My Current State-of-Mind: And What I’m Doing About It For reasons that I’m not yet completely sure, I have been battling a new profound sense of despair since the beginning of the year. And no matter how deeply you try to bury chronic despair, once you have it, there are those occasions when it will inevitably bubble back up to the surface and manifest itself in your demeanor and your ability to function normally. I generally do not consult with therapists,[2] nor do I seek psychopharmacological solutions. I have enough difficulty thinking clearly on my own, without adding mind-altering drugs to the mix. And true to form, I basically tough it out and try to figure things out for myself. This may not be the best option for others however. You ultimately have to decide that for yourself. But nonetheless, I thought it might be useful to share a number of coping and management techniques I have used, in the hope that they might be helpful to others. And they are working, albeit slowly. Perhaps these principles can work for you, if you are experiencing the same. Prayer Soren Kierkegaard, in his Sickness Unto Death (1849), suggested that despair could be understood as comprising three stages: [the first being] Spiritlessness, which applies to those who outwardly seem well-adjusted and successful yet inwardly live in a state of deep and perilous despair.[3] As a Christian believer, I pray daily. And the hope that springs from a God who listens, and who tells us that He will place no burden upon us that is too great for us to bear, is perhaps the greatest help to me in these circumstances. It also is of immense help in fighting off the notion of hopelessness and pointlessness of life that despair often, irrationally, brings with it - because it shows us that there truly is a purpose to what we are going through. Don’t Focus on Yourself – Focus on Others Go out of your way to do acts of kindness for your friends or family - or even complete strangers. Focus on them and their situations, and see if there’s anything you can do to make their day a little bit brighter. When you do interact with others however, for God’s sake don’t be a pill. Don’t make your misery their misery. And don’t look for their pity. They should not even know what you’re going through. Be a blessing to them – not a burden. If all you're going to do is try to solicit their pity for your self-inflicted pain, you're only proving yourself to be a narcissistic bastard. But showing kindness to others will ultimately help your own internal turmoil. It’s counter-intuitive I know, but I have always found this to be true - take your focus off yourself. Also, as long as you can keep your despair contained, you should truly push yourself to go out and meet new people in the true spirit of flânerie. The social interaction will energize you and lift your spirit. It will. It really will. Force Yourself To Keep Moving Forward With Your Life This is very hard to do from the depths of despair. I’ve been there – I know. If you cannot do this on your own, it’s probably time to call a therapist who can help you. But you must do this. You simply cannot allow yourself to become completely consumed by your own perceived self-worthlessness. If you do, your ability to lead a functional life will cease, and you'll find yourself staring off into space - unable to do anything for hours, if not days, at a time. Life is too precious and fleeting to waste it that way. Remember, tomorrow is never guaranteed. Meditate Upon All of the Blessings in Your Life If you can’t help but think about only yourself rather than others during these periods, at least focus on all of the blessings that you presently have in your life (e.g., a caring spouse, wonderful friends, a lovely home, a good paying job, etc.). Don’t focus at all on your misery. In depression, most of it is contrived anyway (although I certainly know it doesn't make it any less real for you). If you truly believe you have absolutely nothing in your life for which you think you should be grateful (which, if that's the case, such a perception should perhaps raise other questions in your mind), then start over and repeat the first three items again. Good Luck – And Get Help If You Need It Despair and flânerie are obviously not compatible over the long term. You have to deal with, or at least manage the first, before you can engage in, and truly enjoy the second. But, as I have found, the act of flânerie itself can assist you in dealing with your depression or despair over the short term. As I stated at the beginning, I sincerely hope that the vast majority or persons reading this post have absolutely no understanding or empathy for the profound experiences it references. But if you do, then you know exactly what I'm talking about, and I sincerely hope that what’s briefly discussed here can ultimately be of some help or comfort to you. If it isn’t – it’s very important that you get other help. If you do think you need professional assistance, and you're not sure where to start, Psychology Today offers a very user-friendly way to find a therapist close to you. Just type in your zip code at the top of the page, and you'll get a good directory of therapists or counselors near you, their areas of specialty, their average rates, and any insurance plans that they accept. Finally, always remember, you’re not alone - even though it feels like it. None of us has a perfect life. As I will continue to assert time and time again - it is most important that you just do whatever it takes to keep moving forward, and to do your absolute best with the hand you're dealt. It will never be exactly the way you want it. __________________________ [1] “Clinical Despair: Science, Psychotherapy and Spirituality in the Treatment of Depression,” by Stephen A. Diamond, PhD.; Psychology Today article posted on-line on March 4, 2011: https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/evil-deeds/201103/clinical-despair-science-psychotherapy-and-spirituality-in-the-treatment. [2] While I do not use therapists – I also do not have any thoughts of suicide. If any such thoughts ever cross your mind, you should see a therapist at once. If you don’t have one - or know how to get one - get yourself to the Emergency Room of your nearest hospital immediately and tell them you need help, or call 911. Do not wait. [3] Op. cit. © 2017 David Nogar All Rights Reserved In his biography of him, James Lincoln Collier writes,”…Louis Armstrong was one of the most important figures of 20th century music. Indeed, a case can be made for the thesis that he was the most important of them all, for almost single-handedly he remodeled jazz and, as a consequence, had a critical effect on the kinds of music that came out of it: rock and its variants; the music of television, the movies, the theater; the tunes that lap endlessly at our ears in supermarkets, elevators, factories, offices; even the “classical” music of Copland, Milhaud, Poulenc, Honegger, and others. Without Armstrong none of this would be as it is [emphasis added]. Louis Armstrong was the preeminent musical genius of his era.”[1] That is why Louis Armstrong matters. But I'd be willing to bet that relatively few today have any real appreciation for the fundamental and profound influence this man has had on American popular music since the 1920's. That influence was widely recognized during the Swing Era, and even into the 1950’s, but not so much today I think - primarily because the passage of time inexorably results in the fading of such memories and awareness. Yes, Louis Armstrong was a genius. An often overused term to be sure, but clearly not in this case. Jazz critic Stanley Crouch once observed that virtually every contemporary pop and jazz vocalist has been influenced by Louis Armstrong, whether they realize it or not. From the 1920's onward, he simply changed forever the style in which American popular songs were sung. An astounding fact, given that his virtuosity was always associated with his cornet, and later trumpet. Louis Armstrong was most likely born in 1897 or 1898 (not 1900, as is often reported) on Jane Alley in New Orleans. He spent most of his youth living at 1233 Perdido Street in the black section of Storyville, in abject poverty. He lived on the same block as the Union Sons' Hall (otherwise known locally as the more accurately described Funky Butt Hall), where the legendary cornetist Buddy Bolden played. Louis remembered listening to Bolden as a small child. In fact, one of Bolden’s most famous numbers, apparently composed by his valve trombonist Willy Cornish, was entitled, “Funky Butt,” later renamed, “Buddy Bolden’s Blues.” It appears that Louis’ father, Willie Armstrong abandoned his wife Mayann either shortly before, or immediately after Louis’ birth, to be with another woman and raise a separate family. He did not appear to be an irresponsible man however, as he worked for the same employer for over 30 years in New Orleans, and attained a modest degree of respectability in the community, remaining with the other woman and providing for this family. Nonetheless, the abandonment by his father left a permanent scar that remained with him until his death. Louis’ mother Mayann also left Jane Alley to relocate to Perdido Street in Storyville when he was an infant. As a result, Louis was mostly raised by his paternal grandmother, Josephine Armstrong, who had been born into slavery in 1858, during his first years. But Louis’ and his mother always retained a strong bond of affection up until her death in 1927. Louis Armstrong makes a return visit to his childhood home in New Orleans. Date unknown, but probably sometime in the late 1930's or 1940's. The neighborhood in Storyville at this time was described as consisting of honky-tonks; dance halls; brothels and saloons; a few churches and grocery stores; and rows of cheap housing, called ‘cribs.’ Music was everywhere, in the form of popular tunes of the day; marches; ragtime; blues; and even plantation songs. Louis Armstrong’s first musical experience was not with the cornet or trumpet, but rather when he formed a vocal quartet and sang on street corners for pennies to help with the family income. During the 1912 New Year's Eve celebrations in New Orleans, he fired a .38 caliber pistol with a live round in it at another youngster who had previously fired a gun at him with a blank cartridge. He was promptly arrested, and on January 2nd was sent to the Colored Waifs' Home run by former soldier Joseph Jones and his wife Manuella, to serve an indeterminate sentence. The Colored Waifs' Home at 301 City Park Avenue in New Orleans circa 1910, to which Louis Armstrong was remanded after 'the pistol incident' on New Year's Eve in 1912. It was at the Waifs' Home where he was given his first musical instrument.... a tambourine! He could not initially read music, and began to learn at the Home. He was later given an Eb alto horn to play, then ultimately a cornet - where his musical aptitude became readily apparent, and he learned music and musicianship under the leadership of Peter Davis. By the time he was released from the Waifs' Home, after approximately two years, he was leading the brass band with the other youngsters who were also affiliated with that facility. After working odd jobs in New Orleans and further developing his craft on the cornet, he ultimately made the transition to becoming a full-time musician in 1918, and remained as such for the rest of his life. Shortly thereafter, he left New Orleans for Chicago, where he was mentored and sponsored by Joe Oliver. Despite such inauspicious beginnings, he went on to have a profound impact on the development of American jazz and blues in a way that ultimately brought incalculable joy and comfort to the entire world throughout the 20th century. The music absolutely would not have been anywhere near the same - or as good - without his influence. By the 1920’s, his genius was already evident. And the seminal, definitive example during his Hot Fives and Hot Sevens period would of course be, “West End Blues,” written by Joe Oliver and recorded by Armstrong on June 28, 1928. You really have to listen to what other popular was sounding like in 1928 to truly appreciate just how amazing, and even revolutionary, this recording was. The first of Louis Armstrong's recordings of West End Blues, made on June 28, 1928 for the Okeh record label. The personnel included Louis on cornet; Earl Hines on piano; Jimmy Strong on clarinet; trombonist Fred Robinson; Mancy Carr on banjo; and Zutty Singleton on drums. From his unaccompanied cadenza opening to his scat vocals to his 4-bar high Bb, it’s instructive to keep in mind how different this was from how everyone else was playing and singing at that time, and more importantly, how it proceeded in a direction that virtually everyone else was going to follow. Perhaps Artie Shaw biographer Tom Nolan illustrates the point best in, “Three Chords for Beauty’s Sake,” in describing Shaw’s reaction to hearing Louis Armstrong for the first time on some Hot Fives records he found in a Cleveland warehouse: “’I couldn’t believe my ears [Shaw said]. No one had done that on a trumpet, before him. No one knows how he got to that. I didn’t understand that, and I still don’t.’ With Armstrong’s West End Blues, Shaw said, ‘I began to see vistas in music, in popular or in jazz playing, that I had not even imagined or conceived of.’”[2] More specifically, Shaw thought that, “Armstrong brought ‘swing’ to the fore: that rhythmic feel that marked what was jazz and what wasn’t. The rhythms and patterns that poured from his horn showed the way to the future….”[3] So by the early 1930’s, through the 1940’s and even into the 1950’s and ‘60’s, those rhythms and styles, with the smooth, forward rhythmic propulsion pioneered by Louis Armstrong that characterizes ‘swing;’ had permeated virtually all of American popular music. Nicely exemplified below even in a blues ballad performed by Louis and Billie Holiday entitled, The Blues are Brewin’, from the 1947 film, “New Orleans.” ____________________________ [1] James Lincoln Collier, Louis Armstrong: An American Genius (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983) p.3 [2] Tom Nolan, Three Chords for Beauty’s Sake (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2010) p.25. [3] Ibid. Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday together in The Blues Are Brewin' from the 1947 United Artists film entitled, "New Orleans." A later example below of Louis Armstrong's improvisational skills while appearing on the Colgate Comedy Hour in 1952. Here he's playing Bugle Call Rag to awaken the troops in place of Reveille during a skit. Louis Armstrong makes a guest appearance on NBC's Colgate Comedy Hour on June 28, 1952 hosted by Bud Abbott and Lou Costello. A fine example of his improvisational skills, and his sharp attack on cornet that he first learned at the Waifs' Home in New Orleans, giving his horn its distinctive sound.

And so, Pops - thank you. Thanks for showing us how to live our lives, no matter our life circumstances or what happens to us. Thank you for sharing your musical genius to bring joy, to inspire, and to uplift the spirits of millions, worldwide. Thank you for always sharing a smile, a laugh, and the music that came from your heart. And thank you for your eternal optimism when you had every right to be bitter and to give up. Thank you for resisting the political and cultural cynicism that is now consuming the rest of us. The world’s a better place for the time you spent in it. What a wonderful world.

© 2017 David Nogar All Rights Reserved |

Author

David Nogar worked in railroad operations for almost 50 years until retiring from the transportation business in early 2023.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed